A decade which started with Gascoigne's tears and ended with Solskjaer's glorious toe poke; the decade more importantly when technical ability surpassed expectations, when the class of the 90s outgrew the 20th century.

The class of the 90s defied expectations with a 'whatever you can do I can do better' attitude which football was only just acclimatising itself to. Ronaldo hit 34 goals in 37 appearances for Barcelona in the 1996/97 campaign, Roberto Carlos hit a stunning banana kick and an English 18-year-old had the audacity to skip past an Argentine defence before smashing home a memorable goal.

The class of the 90s developed on the talent of previous generations. Figo and Beckham reinvented the capabilities of a wideman with an emphasis on precise delivery. Cafu and Carlos built on the model full back set out by Carlos Alberto adding a greater goal threat, whilst Roberto Baggio slivered his way through the smallest of gaps possible. Raul emerged as the prodigal son of Real Madrid, Del Piero the equivalent for Juventus- instinctive strikers, who could perfect the tap in and the finesse finish. The introduction of the Champions League showcased this abundance of attacking flair coming to the fore.

It's no easy feat to be at the top of your game for three or four years at a time, arguably the minimal period of sustained brilliance to be considered one of the greats of your decade. Staying clear of injury is vital; had it not been for injury some of the decade's most gifted stars could have achieved so much more then they did - both Baggio and Ronaldo's knees struggled to keep up with the rest of their bodies.

The right manager plays a role too. For roughly fours years Ronaldinho captivated the Catalan crowds, but when vice seduced him Frank Rijkaard did little to halt it ruining the troubled genius. Had Ronaldinho chosen Manchester United and Alex Ferguson his chances of a prolonged peak would no doubt have been heightened.

Playing in a successful side is a often a necessity. It's with the Madrid's and Milan's that you win trophies and a individual needs some silverware to show for his endeavours. But the 90s saw the rise of the individual, the ego, the No.10.

The football maverick has been reincarnated many a time, both before and after the 90s - think Best and Balotelli. And the 90s had the privilege of witnessing the likes of Romario, Ginola and Cantona liven up the game on and off the field. Romario didn't do training, even Sir Bobby Robson could not implement a harder work ethic. The distractions of the game surfaced during the 90s but were still in a relatively harmless stage. The Liverpool suits in 96 and their infamous Christmas party in 98 were signs that player power was growing.

Maradona was sublime, because he could take a decent but by no means special Argentine side and win them the World Cup. During the 90s the ability to carry a side was seen more frequently. Baggio waltzed Italy to the World Cup Final in 1994, Cantona pulled United over the line come May 96 and Bierhoff stunned the Czechs a few months later, taking matters into his own hands with a masterclass substitute performance.

The class of the 90s developed on the talent of previous generations. Figo and Beckham reinvented the capabilities of a wideman with an emphasis on precise delivery. Cafu and Carlos built on the model full back set out by Carlos Alberto adding a greater goal threat, whilst Roberto Baggio slivered his way through the smallest of gaps possible. Raul emerged as the prodigal son of Real Madrid, Del Piero the equivalent for Juventus- instinctive strikers, who could perfect the tap in and the finesse finish. The introduction of the Champions League showcased this abundance of attacking flair coming to the fore.

It's no easy feat to be at the top of your game for three or four years at a time, arguably the minimal period of sustained brilliance to be considered one of the greats of your decade. Staying clear of injury is vital; had it not been for injury some of the decade's most gifted stars could have achieved so much more then they did - both Baggio and Ronaldo's knees struggled to keep up with the rest of their bodies.

The right manager plays a role too. For roughly fours years Ronaldinho captivated the Catalan crowds, but when vice seduced him Frank Rijkaard did little to halt it ruining the troubled genius. Had Ronaldinho chosen Manchester United and Alex Ferguson his chances of a prolonged peak would no doubt have been heightened.

Playing in a successful side is a often a necessity. It's with the Madrid's and Milan's that you win trophies and a individual needs some silverware to show for his endeavours. But the 90s saw the rise of the individual, the ego, the No.10.

The football maverick has been reincarnated many a time, both before and after the 90s - think Best and Balotelli. And the 90s had the privilege of witnessing the likes of Romario, Ginola and Cantona liven up the game on and off the field. Romario didn't do training, even Sir Bobby Robson could not implement a harder work ethic. The distractions of the game surfaced during the 90s but were still in a relatively harmless stage. The Liverpool suits in 96 and their infamous Christmas party in 98 were signs that player power was growing.

Maradona was sublime, because he could take a decent but by no means special Argentine side and win them the World Cup. During the 90s the ability to carry a side was seen more frequently. Baggio waltzed Italy to the World Cup Final in 1994, Cantona pulled United over the line come May 96 and Bierhoff stunned the Czechs a few months later, taking matters into his own hands with a masterclass substitute performance.

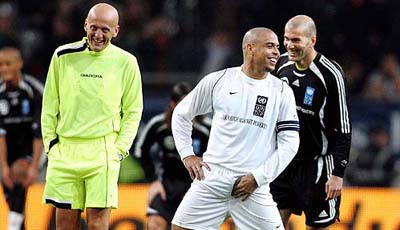

Top of the class were Ronaldo and Zidane.

Four goals and three assists at France 98 confirmed his status as the deadliest forward in the world. Surrounding himself with the best playmakers in the world, the record of almost a goal a game at each club meant Ronaldo bought silverware to any team. What was impressive was his ability to swap Spain for Italy with such ease, scoring goals against notoriously rigid defences.

Zidane's brilliance was only truly highlighted in 1998, with a firm forehead and a 3-0 rout of Brazil on home soil. Zidane's double in the 1998 World Cup Final in France signalled what would become a habit of performing on the big occasions. One of the most graceful footballers of all time, his tenacity was deceptively patient, confident of producing a moment of magic in the 89th minute when required.

A stain on his reputation was the 1997 Champions League Final, when Juventus succumbed to Borussia Dortmund 3-1. Zidane was subdued by Paul Lambert, who must wish that Barry Bannan possessed the discipline to do the same. And when Ronaldo faltered at the final hurdle in 98, Zidane took centre stage. Like Ronaldo, Zidane was able to swap Italy for Spain comfortably and eventually outshone Ronaldo at Real Madrid. Madrid took the class of the 90s and assembled a squad of Galaticos.

By the end of the 90s football was ready to embrace the 21st century. Take Ronaldo, a hybrid who consistently displayed all the individual elements of speed, precision, power and ruthlessness. The Van Basten's and Muller's were blessed with and honed their game's upon one or at best two of these elements. But Ronaldo was lethal in any area of the oppositions half, a threat that couldn't be pinned down.

A stain on his reputation was the 1997 Champions League Final, when Juventus succumbed to Borussia Dortmund 3-1. Zidane was subdued by Paul Lambert, who must wish that Barry Bannan possessed the discipline to do the same. And when Ronaldo faltered at the final hurdle in 98, Zidane took centre stage. Like Ronaldo, Zidane was able to swap Italy for Spain comfortably and eventually outshone Ronaldo at Real Madrid. Madrid took the class of the 90s and assembled a squad of Galaticos.

.jpg)